On facts, learning, and reality

What we hold as facts or truth is what we have been told or by some other means gone out of our way to learn. As you learn more your idea of what is true changes. Your reality is not reality (nor mine), but the set of things that you know and accept.

As a child you learn to count starting with one. The notion of zero isn’t introduced to most children until they are older. The little number line sitting on your desk grows a little longer with zero starting at the beginning. Then you learn about negative numbers and the start of the number line isn’t so simple anymore. You may learn about fractions. You may learn about real numbers. You may even learn about complex numbers. With each step your notion of what numbers are is growing. Human-created abstractions become increasingly complex as we need to find more ways to represent data and the world. There are even hypercomplex numbers that very few people learn because it’s generally not relevant to them. However, when building 3D games they become very important.

This shifting of reality that happens in your brain every time you learn some new piece of data can be staggering. Every time I learned something new I felt almost lied to previously. My notion of truth had shifted and my understanding of the world around me along with it. It seems almost obvious now that the set of natural numbers isn’t adequate for representing all situations. However, it took years for me to process that the set of natural numbers is infinite, but it’s smaller than the set of irrational numbers between 0 and 1.

This notion of truth and facts can be hard to internalize. You may know a lot, but it is most likely incomplete. Even if you some how manage to learn everything possible about a given subject there are likely gaps of things that we as humans haven’t yet learned.

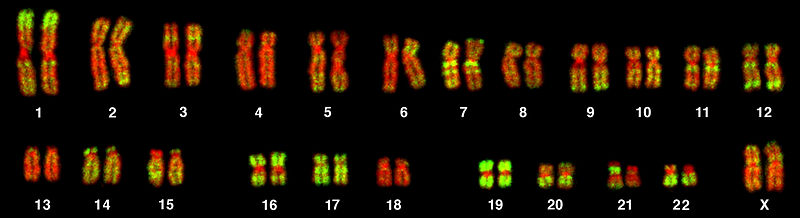

In high school biology class you probably learn that humans have 22 pairs of autosomes and 2 sex chromosomes. You probably learn that humans have either XX or XY chromosomes and you also probably learn that these chromosomes determine if someone is male or female. You learn that a genotype is the genetic data and a phenotype the expression of these genes. This, however, is only a small part of the picture. It’s the natural numbers starting from 1.

In most cases people are born with 2 sex chromosomes. However, it can be more or less. 1 in 1000 phenotypic females will have three X chromosomes (trisomy X). Most of them will never be aware of this. This is only one of the many chromosomal variations that exist:

- XXY Klinefelter syndrome (1:500 to 1:1000 phenotypic males)

- XYY (1:1000 phenotypic males)

- XO Turner syndrome (other chromosome is missing or malformed) (1:5000 phenotypic females)

- XXXX (100 cases reported)

- XXXXX (25 cases reported)

I fully expect that the list above is not complete, but highlights some of the variations that exist despite sex chromosomes to be largely assumed to be simple and binary. Very few things are so cut and dry.While I describe the above as being in phenotypic males and phenotypic females even that is inaccurate. Genotype and phenotype do not always match (intersex). There is even a case in which a predominately 46,XY woman (that is an individual with some XX cells and XY cells) underwent typical female development and even went on the have two unassisted pregnancies. Most of us don’t know what our sex chromosomes are. You may have held that your reality is that you have XX or XY chromosomes, but that might not be your reality. As a side note gender identity is something entirely different and complex on it’s own.

All of this matters. These chromosomes are people. These people are complex, and your reality might not match their reality.